North Carolina’s commitment to providing an equal public education to all students within the state began in 1776, when it included the right to public education in its original constitution. Following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954, many Southern states engaged in immediate backlash, publicly proclaiming that they were not giving up their segregated system of schooling. While North Carolina’s approach to desegregation was less violent than other Southern states, it was by no means progressive, at least immediately following the Brown decision. However, 20 years after the Brown ruling, North Carolina would be recognized nationwide as the blueprint for successful integration strategies.

This timeline explores the policies, court cases, and important historical events that shaped not only school desegregation in North Carolina, but also the resegregation that has occurred in more recent years. This project attempts to highlight the lived experiences and stories of those who lived through desegregation, and fought to create equal schooling opportunities for all North Carolinians. To learn more about any of the topics covered in this timeline, please consult our resources page and literature review. We would like to thank Jenn Ayscue, Sandra Conway, Danita Mason-Hogans, and the UNC Southern Oral History Program for their support, expertise, and guidance throughout this project.

Timeline and literature review created by Flood Center School Desegregation Fellow Emma Miller.

School Desegregation and Resegregation in North Carolina

On May 18th, 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson ruled that racial segregation was constitutional under the “separate but equal” doctrine.

On July 26th, 1948, President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, desegregating the American military and opening up opportunities for desegregation in every facet of American life.

On March 27th, 1951, the McKissick v. Carmichael decision ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, four Black students seeking admission to UNC’s Law School, effectively desegregating the Law School. This ruling gave the precedent for other forms of higher education across the state to desegregate.

Plaintiff Floyd McKissick, the first Black student at UNC Law on why he chose UNC to help desegregate:

On May 17th, 1954, the Supreme Court ruling Brown v. Board of Education of Topkea struck down the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. Renowned hotojournalist Alex Rivera discusses the importance of the Brown decision and the impact that it had on Black communities in North Carolina:

In the summer of 1954, Governor Umstead responded to the Brown decision by creating the Governor’s Specialty Advisory Committee on Education, led by Thomas Pearsall, an attorney and politician from Rocky Mount, NC. Umstead claimed that the goal of the committee was to “establish a policy and a program which will preserve the State public school system by having the support of the people.”

On March 30th, 1955, the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Pupil Assignment Act, a law that delayed integration by shifting the responsibility of desegregation from the state to local school boards. It also removed any references to race in all school laws.

After the initial Brown decision in 1954, the Court convened to rule on the implementation of the original ruling. The Court decided that the decision should be implemented with “all deliberate speed.”

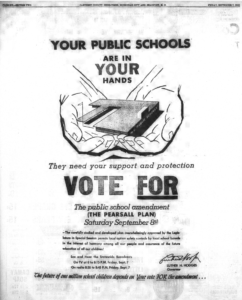

In April 1956, the Pearsall Committee released the “Pearsall Plan to Save Our Schools”, a report with recommendations based on the research that members of the Pearsall Committee had conducted. The plan included voluntary school assignment, a tuition grant system, and eliminated attendance requirements for students who were assigned to an interracial school against their wishes.

On September 4th, 1957, Dorothy Counts becomes the first Black student to attend a predominantly white school in North Carolina, Harry Harding High School in Charlotte. Counts was met with intense resistance and violence from white students, parents, and administrators alike. Dorothy Counts discusses her first day of school:

In February 1960, four Black students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical college sat at the segregated whites-only lunch counter of Woolworth’s five-and-dime in Greensboro, North Carolina. This launched the sit-in movement across the nation, and began the process of the desegregation of public spaces across the South.

In September 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama was bombed, killing four Sunday School children. This event, in combination with earlier instances of violence in Birmingham that spring, shocked the nation and made Civil Rights in America an international issue.

In July 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into place, outlawing discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin. Titles IV and VI dealt explicitly with education: Title IV commissioned the Coleman report on educational opportunity and equity, and Title VI permitted the withholding of funds from school districts who refused to comply with the Brown ruling.

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) is passed in April, 1965 as part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty. This Act gave the Civil Rights Act the ability to actually withhold federal funding for noncompliant districts.

In 1966, a report titled The Equality of Educational Opportunity (also known as the Coleman Report) is released. This report was commissioned by the Civil Rights Act to study educational opportunities and outcomes for students of color. The report found that there was a significant achievement gap between Black and white students. The Coleman Report would continue to be pivotal in many desegregation Supreme Court cases.

In April 1968, Civil Rights leader MLK Jr is assassinated. As protests spark across the country, the Nixon campaign seizes on the idea of “law and order”, and public opinion shifts away from favoring increased civil rights for Black Americans.

In April 1968, President Johnson passes the Fair Housing Act, which prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, sex. This was a crucial step for school desegregation, as it is often a student’s neighborhood that determines where they will attend school.

Richard Nixon is elected as president, campaigning on the “Southern Strategy”, focusing on rhetoric of “law and order” and increasing racial fears of white Republicans. Nixon would go on to appoint four Supreme Court justices that would make key decisions regarding desegregation.

In July 1969, Godwin v. Johnson ruled that the state of North Carolina was in charge of desegregating schools–not the individual localities.

Civil Rights leader and school desegregationist Dr. Dudley Flood began his position at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction on January 2nd, 1970. Dr. Flood, along with his colleague Gene Causby, traveled across the state as representatives of DPI to meet with school districts who were struggling with how to desegregate their local schools. Here, Dr. Flood discusses the responses that communities had to desegregation plans, specifically school closures:

Listen to Part I and Part II of the full interview, or read the full interview transcript.

[learn_more caption=”Audio Transcript”] “There was no one way that you would characterize their behavior, but there were several things that you could anticipate. The first is that you’re asking people to make a change, and it’s very rare that you meet anybody who wants to make a change. So you had to devise a matter of analyzing change for them. And there are three elements of that that you have to analyze. First of all, how pleased are you with what you now have? Secondly, what is the specific change you’ve been asked to make and thirdly what will be different and better? When you shall have made that change, unless those three things are in place, you continue to have this kind of annuity between what the law says or the policy says and what people are actually going to do. If, for example, your plan called for closing the school, which it often did, you closing the black school or move all the kids to the previously white school. They are grandmothers and mothers sometimes who aren’t in that school. It was the definition they had for what school is and then many communities, particularly in many black communities, the school’s the center of the community. It was the one thing around which everyone coalesced. It was the social life, it was the educational life and everything else that was meaningful to them. So the identity with that school was way beyond just education, way beyond that.”[/learn_more]

In April 1971, the Swann case challenged the Pearsall Plan and ruled that busing was a legitimate and useful tool for desegregation. School districts across the nation would cite this ruling for decades to come when implementing their own busing plans.

In July 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in Miliken that schools were not responsible for busing students to other schools across district lines. This set a long precedent that schools could not desegregate across district lines–a larger issues for de facto segregated districts in the North that could have dozens of districts within a single county.

In January 1991, Board ruled that once a school district became racially “unitary”, schools that were no longer identifiably “Black” or “white”, then they could be released from court-mandated desegregation practices such as busing.

In May 1994, five districts in low-wealth counties filed a lawsuit against the state, arguing that despite the fact that they were being taxed at higher-than-average rates, their school districts did not have enough funds to provide an equal education for their students. 25 years later, the Leandro case continues to be one of the biggest issues within North Carolina education policy. Learn more about the Leandro case here.

The Charter Schools Act of 1996 is passed, authorizing the formation of up to 100 charter schools in the state of North Carolina. The act also limited districts by stating that no district could have more than 5 charter schools. This act signified the beginning of the school choice movement in NC, and the provision of alternative options to the traditional public school.

In 1997, the North Carolina Supreme Court declared that North Carolina was obligated to provide its students a “sound, basic education.”

In 1998, the nonprofit group North Carolina Foundation for Individual Rights filed a lawsuit to attempt to block the state’s diversity requirement for charter schools. NC laws state that the racial makeup of charter schools must “reasonably reflect” the community they serve. As a result of this lawsuit, North Carolina decided not to continue to enforce this racial diversity rule. At the time of the lawsuit, North Carolina’s charter schools served predominantly Black students.

In 1997, William Capacchione, a white parent, filed a lawsuit against CMS on behalf of his daughter Christina stating that she was not admitted to a magnet school of her choice due to her race. In 1999, the judge ruled that CMS must stop using race as a category for pupil assignments to schools within the district. The judge also ruled that Charlotte has been compliant with the Swann ruling and “has achieved unitary status in all respects,” and no longer needs to be under court-ordered desegregation.

Following the Capacchione case and the declaration of CMS as “unitary”, a group of Black families filed a motion to reactivate the Swann case, arguing that CMS had not officially reached unitary status, and that maintaining desegregated schools was crucial to the quality of their children’s education. However, the United States Court of Appeals Fourth Circuit found that CMS had indeed ended their segregated system of schooling, and had achieved unitary status.

This second Leandro ruling affirmed the “Leandro Tenets” necessary to receiving a sound, basic education. It also ruled that the state was in violation of providing a sound, basic education, and that it was not possible to achieve this by transferring educational responsibility to localities.

Parents Involved in Community Schools (PICS) v. Seattle ruled that the use of student’s race in pupil assignment was unconstitutional. This would affect school districts across the nation that were using the racial identity of a student as a factor in school assignment as a measure of desegregation.

In February 2011, Senate Bill 8 was passed, lifting the 100 charter school cap put in place by the previous 1996 Charter School Act. The cap was lifted in order to receive federal funding from the Race to the Top program. This led to a rapid increase in charter schools across the state, which have demonstrated in recent years to be increasingly more segregated than traditional public schools, and in North Carolina, serve primarily white students. In these districts, charter schools effectively segregate traditional public schools.

In September 2015, the North Carolina General Assembly passes HB 334, which permitted the creation of a weighted lottery system to be used by charter schools to promote socioeconomic diversity within the school. As of the 2018 school year, only 4 charter schools in the state have utilized this program.

In November 2017, NC Governor Cooper issued Executive Order 27, which created the Commission on Access to Sound Basic Education. The mission of the Commission is to assess the state’s ability to staff schools with highly effective teachers and principals, and the state’s commitment to providing adequate resources for all students.

Judge David Lee, the judge presiding over the Leandro case and the person responsible for making sure that North Carolina implements the decision in the case, ordered an independent report on the state of education in North Carolina. Lee commissioned WestEd, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research agency to study the issue and recommend a plan of action for the state.

In December 2019, WestEd released its report to the public. The report titled Sound Basic Education for All: An Action Plan for North Carolina, included 8 detailed recommendations of how North Carolina could comply with the Leandro orders.

Comprehensive Remedial Action Plan

On March 15th, 2021, the comprehensive remedial action plan for the Leandro case was submitted to the Superior Court. This plan addresses the ways in which North Carolina can meet its constitutional obligation to provide every student with a sound, basic education.